August, 2009

On a recent hike to photograph vintage WWII-era bunkers in Camp Hero on the tip of Long Island, I was surprised to find some of the entrances relatively unadorned by graffiti. Subjected to many years’ overgrowth since their decommission in the 1980s, the still-visible reinforced concrete egresses seemed perfect for such fun. There was evidence of some vandalism -- which goes with the territory and age of the site -- but in general the semi-remote location must have played a part in the natural preservation of the artifacts. Camp Hero is an anti-destination of sorts, not a place one stumbles upon when looking for the beach. The afternoon was warm and sunny, yet something made me feel uneasy. I wondered what could be more patriotic than enjoying a hot-dog and soft drink, sitting atop an abandoned bunker-cum-picnic area that formerly housed 16-inch artillery under the watchful eye of a football-field-sized radar dish.

I was curious to see the location of The Philadelphia Experiment and The Montauk Project, supposed secret military experiments involving time travel and mind control, both tangential byproducts of the U.S. Navy’s attempts to render ships more difficult to detect in terms of mines and enemy attack. The centerpiece of Camp Hero and its environs is the massive SAGE (Semi-Automatic Ground Environment) radar unit, a local landmark of sorts, often used as a visual reference by fishermen (boaters and fishermen reportedly lobbied to have the structure saved, since it was easier to recognize than the nearby Montauk Lighthouse). Built in the 1960s by the Sperry Corporation, the AN-FPS-35 radar weighs 70-80 tons, stands atop an 80-foot concrete tower and could locate objects up to 200 miles away when active. The robustness of this giant system reflected the “bigger is better” attitudes of the day, manifested in disrupted TV and radio reception in the region, and provided fodder for speculation that its power was harnessed in mind-control experiments on unsuspecting citizens [curiously, the industrial-strength metal operator’s terminals resembling giant retro video-game consoles featured built-in ashtrays]. The technology, cutting-edge at the time, became obsolete as cold war strategies shifted from bomber- to missile-centric delivery vehicles.

I was curious to see the location of The Philadelphia Experiment and The Montauk Project, supposed secret military experiments involving time travel and mind control, both tangential byproducts of the U.S. Navy’s attempts to render ships more difficult to detect in terms of mines and enemy attack. The centerpiece of Camp Hero and its environs is the massive SAGE (Semi-Automatic Ground Environment) radar unit, a local landmark of sorts, often used as a visual reference by fishermen (boaters and fishermen reportedly lobbied to have the structure saved, since it was easier to recognize than the nearby Montauk Lighthouse). Built in the 1960s by the Sperry Corporation, the AN-FPS-35 radar weighs 70-80 tons, stands atop an 80-foot concrete tower and could locate objects up to 200 miles away when active. The robustness of this giant system reflected the “bigger is better” attitudes of the day, manifested in disrupted TV and radio reception in the region, and provided fodder for speculation that its power was harnessed in mind-control experiments on unsuspecting citizens [curiously, the industrial-strength metal operator’s terminals resembling giant retro video-game consoles featured built-in ashtrays]. The technology, cutting-edge at the time, became obsolete as cold war strategies shifted from bomber- to missile-centric delivery vehicles.

Camp Hero was designed to resemble a sleepy New England fishing village in order to fool potential Nazi U-boat spies who were reportedly active in the region. The concrete bunkers and lookout posts went so far as to have fake windows painted on them, added ornamental roofs (replete with imitation dormers) and even lifelike concrete clapboards. The base’s gymnasium was designed to resemble a church -- steeple included -- in an odd dysbrutalist twist (leCorbusier’s Chapel of Nôtre Dame du Haut at Ronchamp, considered the first Postmodern building, features massive curved concrete walls, resembling those of bunkers with bomb-deflecting features). Walking the perimeter of the restricted areas and the grounds populated with abandoned barracks, parking lots and miscellaneous concrete footings, I felt an uneasiness or disorientation, heavy like a cloud. Freud called this feeling uncanny, linked to “…intellectual uncertainty; so that the uncanny would always, as it were, be something one does not know one’s way about in. The better oriented in his environment a person is, the less readily he will get the impression of something uncanny in regard to the objects and events in it.” I was reminded of the term unheimlich (translated: unhomely), Anthony Vidler’s description of a “sense of lurking unease…an uncomfortable sense of haunting.” Always partially visible, through the trees, atop a ridge or even over my shoulder was the lurking eye of the SAGE dish. A network of access roads and trails allowed hikers to explore most of the area, save for those restricted parts.

Camp Hero was designed to resemble a sleepy New England fishing village in order to fool potential Nazi U-boat spies who were reportedly active in the region. The concrete bunkers and lookout posts went so far as to have fake windows painted on them, added ornamental roofs (replete with imitation dormers) and even lifelike concrete clapboards. The base’s gymnasium was designed to resemble a church -- steeple included -- in an odd dysbrutalist twist (leCorbusier’s Chapel of Nôtre Dame du Haut at Ronchamp, considered the first Postmodern building, features massive curved concrete walls, resembling those of bunkers with bomb-deflecting features). Walking the perimeter of the restricted areas and the grounds populated with abandoned barracks, parking lots and miscellaneous concrete footings, I felt an uneasiness or disorientation, heavy like a cloud. Freud called this feeling uncanny, linked to “…intellectual uncertainty; so that the uncanny would always, as it were, be something one does not know one’s way about in. The better oriented in his environment a person is, the less readily he will get the impression of something uncanny in regard to the objects and events in it.” I was reminded of the term unheimlich (translated: unhomely), Anthony Vidler’s description of a “sense of lurking unease…an uncomfortable sense of haunting.” Always partially visible, through the trees, atop a ridge or even over my shoulder was the lurking eye of the SAGE dish. A network of access roads and trails allowed hikers to explore most of the area, save for those restricted parts.

My map indicated several trails leading to and around the two large bunkers, so I made a preliminary check of my clothing: shorts, t-shirt, hiking shoes, and noted where to check later for ticks. Due to the wet conditions, they were in abundance, and I became hyper aware of any foliage brushing against me (if you’ve ever experienced the tenacity of tick attached to your person, you’ll understand my caution). One trail was nearby, but I chose to duck through a hole in the chainlink fense and find a shortcut. Foliage and sagebrush brushed my leg. I looked down and back up and saw the antenna, following me like the eyes in some creepy portrait in a Vincent Price movie. I quickly found a marked trail, as indicated on the map, but it wasn’t until I made a complete loop and was back where I began at the access road that I realized I had circled Bunker #2 entirely. Overgrown into an oblong hillock, I missed most of it until I found once again the entrance, sealed and tagged lightly with graffiti.

My map indicated several trails leading to and around the two large bunkers, so I made a preliminary check of my clothing: shorts, t-shirt, hiking shoes, and noted where to check later for ticks. Due to the wet conditions, they were in abundance, and I became hyper aware of any foliage brushing against me (if you’ve ever experienced the tenacity of tick attached to your person, you’ll understand my caution). One trail was nearby, but I chose to duck through a hole in the chainlink fense and find a shortcut. Foliage and sagebrush brushed my leg. I looked down and back up and saw the antenna, following me like the eyes in some creepy portrait in a Vincent Price movie. I quickly found a marked trail, as indicated on the map, but it wasn’t until I made a complete loop and was back where I began at the access road that I realized I had circled Bunker #2 entirely. Overgrown into an oblong hillock, I missed most of it until I found once again the entrance, sealed and tagged lightly with graffiti.

One of the qualities of the bunkers that initially attracted me is the surface of the concrete itself. An inherently humble building material, concrete is usually poured into forms, and faithfully records the individuality of each piece of wood used. Fine detail, down to grain swirls and splinters, chips and dents are all there upon close inspection, indicating a common source of wood in that particular area. Stepping back, I can see the angle and direction of the wood, revealing various patterns. At this distance I am aware of the overall shape and mass of the structure; but, by virtue of the fact that these bunkers were sometimes disguised as houses, it was possible to regard them as both architectural structures and as interesting objects.

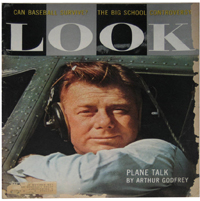

Evidently in 1964, while flying near Philadelphia, the entertainer and radio/TV host Arthur Godfrey encountered an UFO off the wing of his small aircraft. Radio contact confirmed no other airplane traffic in the vicinity, and yet the fast-moving object continued its escort of Godfrey’s plane, even avoiding evasive maneuvers. “The darndest thing was,” Godfrey later commented, “I banked hard starboard and spilled a large coffee all over my lap, and the thing was right back again, this time off my left wing-tip. I thought I had polished it off, but whatever it was, it was as tenacious as my dear old mother on my case to clean up some spilled guava juice (my favorite).”

Evidently in 1964, while flying near Philadelphia, the entertainer and radio/TV host Arthur Godfrey encountered an UFO off the wing of his small aircraft. Radio contact confirmed no other airplane traffic in the vicinity, and yet the fast-moving object continued its escort of Godfrey’s plane, even avoiding evasive maneuvers. “The darndest thing was,” Godfrey later commented, “I banked hard starboard and spilled a large coffee all over my lap, and the thing was right back again, this time off my left wing-tip. I thought I had polished it off, but whatever it was, it was as tenacious as my dear old mother on my case to clean up some spilled guava juice (my favorite).”

Godfrey’s years of training as a radio show host were of little help except for bringing belly laughs to the air traffic control operators manning the radars that evening. As recounted by Merlin Blauser III, “we were in stitches. Hearing that familiar voice talking about a UFO in the same breath as his mother just sent chills up my funny bone. He was such a dickens.” Luckily, other pilots involved in midair near-misses either dismissed the controllers’ blunders as pranks or merely assumed the banter was just so much re-hashed stand-up material. Regardless, hearing that voice seemed to trigger warm chuckles as well as hair-raising titters.

The phenomenon of qualia has been described as an “unfamiliar term for something that could not be more familiar,” like the experience of the color red, for example. The term is derived from Latin, meaning “what sort” or “what kind,” and involves the disconnect (or perhaps connect) between the mind and the body. The color red can be described in terms of its physical properties, yet how can it be adequately described to, say, a person born without sight? According to some, qualia are unobservable in others, and unquantifiable in us, making them utterly personal in nature. This makes it tricky when answering claims of strange things afoot during any military experiments in the region. One person’s word against another offers little in the way of solid proof, especially when dealing with such slippery mental and physical states. Still, when walking around this storied area, I couldn’t help but feel something…very difficult to put into words.